Woven Songs raises questions about something as concrete as the very earth we walk on every day and how we live our lives on it. The earth that harbors at once a profane and a magical symbolism, a material foundation for both, holiness and life and death, right beneath our feet. Woven songs is a series of artworks and artistic interventions to be featured in the different exhibitions of the Luleå Biennial and on public sites in Norrbotten County from November 2020.

The project poses a series of questions that concern something as matter-of-fact as the earth, and how we live our lives there. The earth is at once a symbol of the sacred and the profane, and the material foundation for life and death, right under our feet. In various ways Woven songs grapples with suspending a western logic in which the magical perspective has been separated from the level of everyday life. It turns the ear to the ground and listens to the rumble, traumas and songs that are awoken.

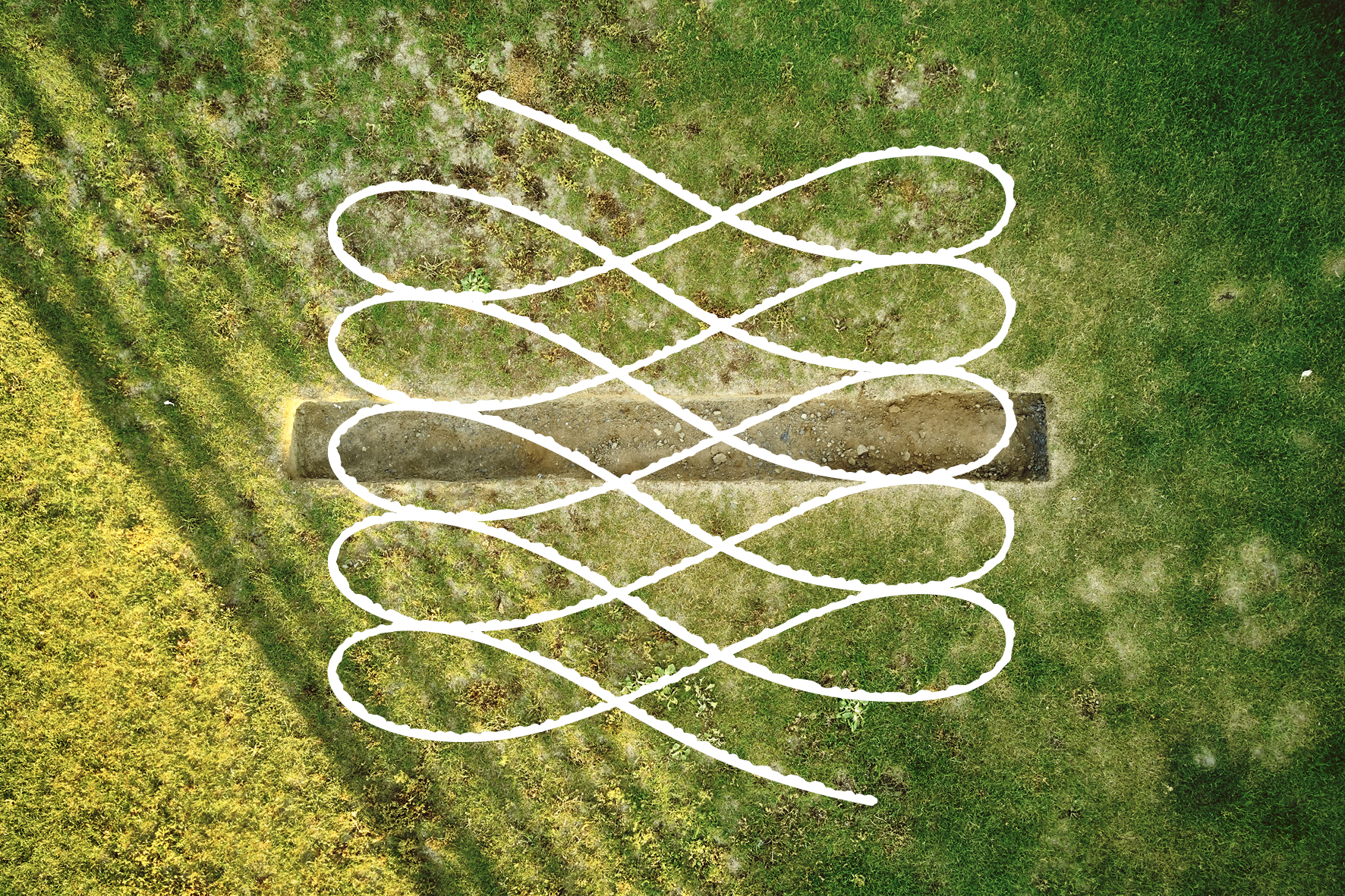

At Välkommaskolan in Malmberget, this line of enquiry meets a local landscape collapsing from the effects of the mining industry. The school has already been evacuated and will be demolished shortly after the end of the exhibition. At Vita Duvan in Luleå a sonic installation speaks to the unifying power of song and the women’s history contained within the walls of the former prison. At Luleå Art Gallery, we are introduced to the story of an enigmatic magician whose rotting magic factory on the outskirts of Jokkmokk is being reclaimed by nature. At the Luleå University of Technology and at the magnificent waterfall Storforsen, sculptural forms in the shape of fists burst out of the ground as if in revolt. Towards the end of the biennial, a choreographic work will praise the earth in a wild ritual where bodies, plants and liquids collide and become one with one another.

Woven songs is a programme of works and events in collaboration with Public Art Agency Sweden, curated by Edi Muka in dialogue with Karin Bähler Lavér, Emily Fahlén and Asrin Haidari. It crops up within the biennial’s various exhibitions as well as in public places in Norrbotten.

Participating artists: Linnea Axelsson, Kapwani Kiwanga, Maria W. Horn, Ingrid Ogenstedt, Hanna Ljungh in collaboration with Mattias Hållsten, Elisabete Finger and Manuela Eichner in collaboration with Bárbara Elias, Danielli Mendes, Josefa Pereira, Mariana Costa and Patrícia Bergantin, Aage Gaup and Isak Sundström.

Curator text by Edi Muka

Some people love to divide and classify, while others are bridge-makers, weaving relations that turn a divide into a living contrast, one whose power is to affect, to produce thinking and feeling.*

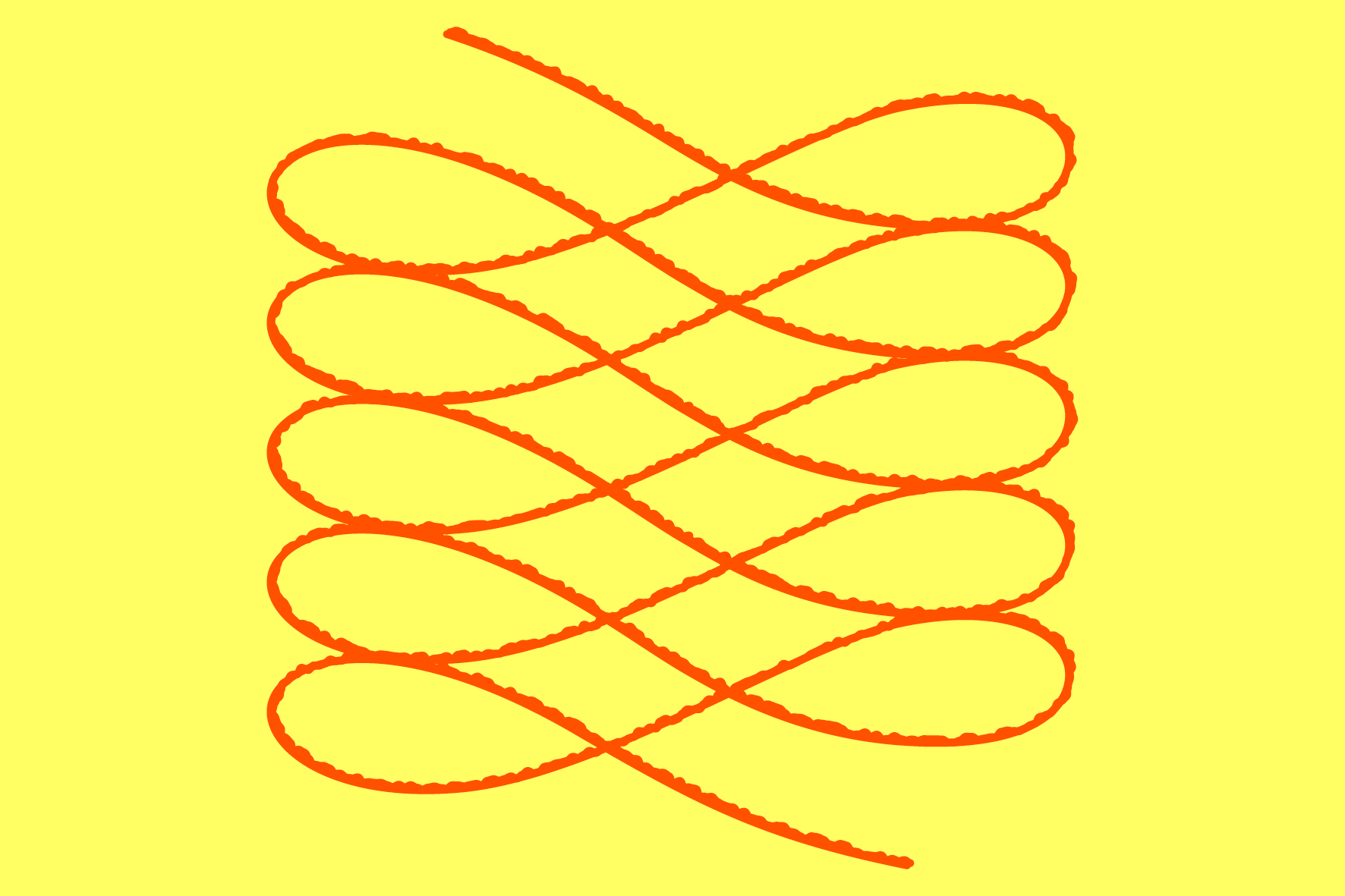

Somewhere in the Peruvian Amazon along the river Ucalayi, live the Shipibo peoples. They are known for their “ikarays”, healing song patterns that are also referred to as Woven Songs. In their worldview the universe is made, or one can say woven, of songs. Everyone and everything in it has its own song pattern that the Shipibo healers sing in their healing rituals and weave in their clothes. When someone or something is unwell, their song pattern has been wrapped in twine. It needs to be untwined and joined in the harmony of the worlds through the singing. For singing has the power to heal, it has the power to weave a person or a situation back into the oneness of the universe. Only then, when the balance of the universe is restored, is the healing complete.

The new millennium has brought to the fore multiple challenges dominated by the climate change and intensifying social tensions. The damage we’ve caused to the planet has resulted in a growing demand to question the dominating worldview and an increased awareness towards indigenous peoples cosmological thinking. Yet, this hasn’t slowed down devouring forest fires and devastating extraction endeavors. On the social plane, new social movements such as Black Lives Matter have gained a global foothold. But tensions are running high as such movements call into question the colonial foundation of western modernity. As of late, we’re also living through unknown scenarios dictated by the spread of a global pandemic. This has profoundly disrupted the “normality” of the everyday and weakened democracy, but it has also shown that other ways of organizing life and society are possible.

It could seem surprising and incomprehensible that these developments are taking place in the 21st century. However, a closer look at the historical entanglements of events would clearly tell us how destructive many of the legacies, systems and institutions, that together forged the foundations and continue to maintain the status quo of the dominating worldview, have been.

The edifice of western modernity was built on the colonial paradigm. Based on the reduction of the world into “objective reality” its system of ideas gave life to the irreconcilable divide between “nature” and “culture”. A divide, to quote Isabelle Stengers, “across which some felt free to study and categorize the others (…)”, and where “(…)“we” on our side, presume to be the ones who have accepted the hard truth that we are alone in a mute, blind, yet knowable world – one that is our task to appropriate”*. On the other side of the divide ended everyone and everything else that didn’t fit in the same mold – that of the human white male. The historical entanglements of this system of ideas reach deep into our present. They are complex and not possible to dismiss and still shape the social reality of the 21st century. Global in scale and character, they play out and affect local contexts in specific ways, leaving behind both visible and invisible marks everywhere, in and around us.

“It matters what stories make worlds, and what worlds make stories”*

In no other part of Sweden has the colonial paradigm left as clear a mark as in the geo-history of Norrbotten. Mining and extraction – the motor of the colonial project – hollowed the earth and uprooted and dispossessed indigenous peoples. But they also gave rise to entire new societies, cities and communities. The fostering and disruption of relations, old and new, mirror the mutual relation between the promise of prosperity and the constant threat of utter devastation, as reified by the gigantic pit in Malmberget. An irreversible scar on the earth itself, the pit bears witness to our estranged relationship to nature and its effects on the lives and relations between all the peoples, groups and communities that inhabit the area. And similar or parallel stories run through and still continue to evolve around many other mines, rivers and forests everywhere in the world.

So what can these local stories and their interconnections reveal about the worldview that has formed the global social reality we live in? Are the indigenous peoples’ cosmologies the knowledge systems “we” on our side of the divide Stengers talks about, need to turn to, to challenge our understanding of the world and ourselves? Is it at all possible to translate or reconcile these diverse worldviews, or would this be yet another act of appropriation? How to relearn the magic of the world as a way to repair our relationship to the living earth and also mend our relations to each other?

Woven Songs raises questions about something as concrete as the very earth we walk on everyday and how we live our lives on it. The earth that harbors at once a profane and a magical symbolism, a material foundation for both, holiness and life and death, right under our feet. The project embarks on questioning the western logic that separates the magical perspective from our idea of reality, understanding the earth as dead matter that must be claimed and appropriated. The invited artists explore the systems, institutions and legacies that have enabled entire social realities, but that have also left deep scars on individuals, communities and on the earth itself.

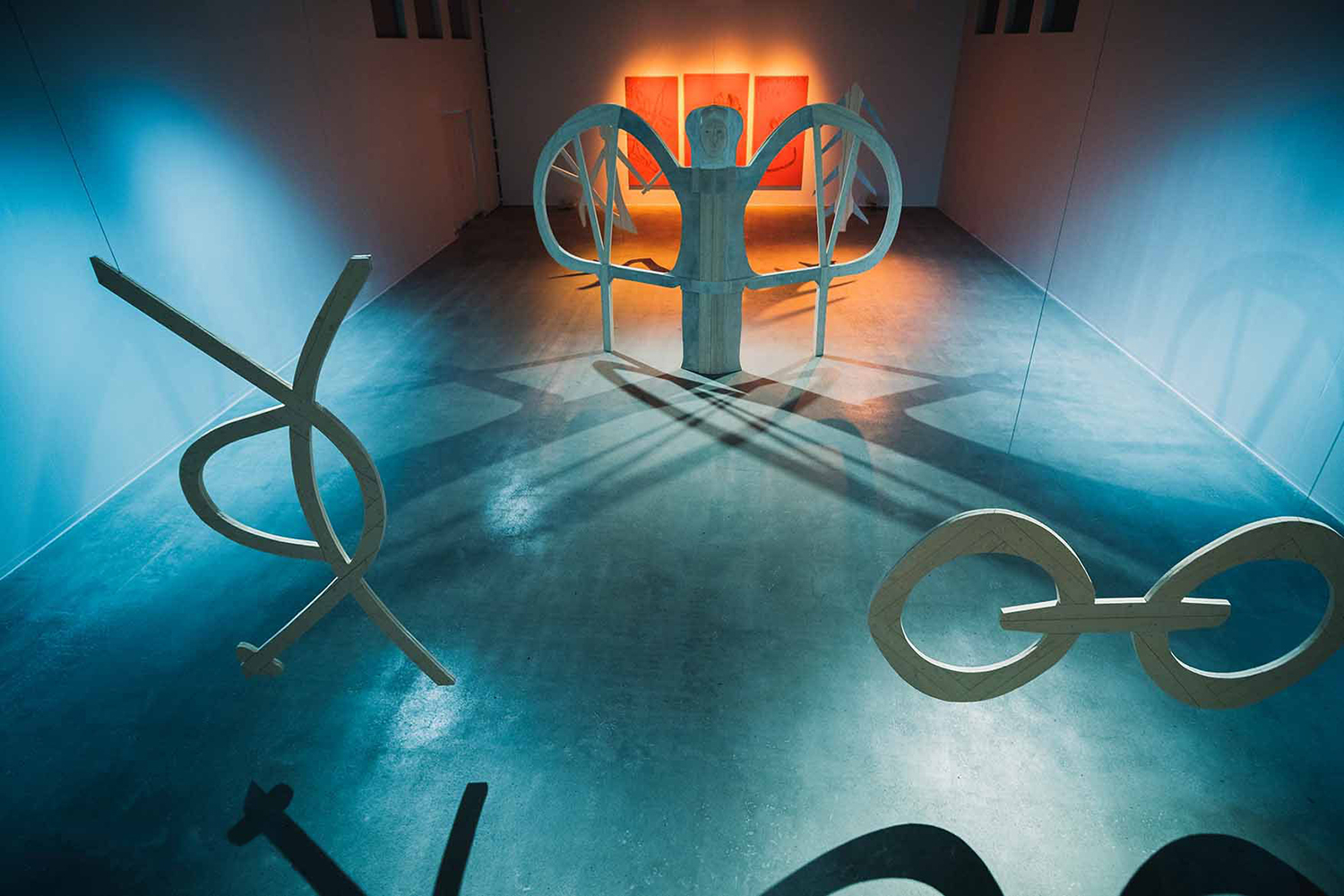

Departing from the empty building of Välkommaskolan in Malmberget, a number of works connect to the history of the place and to the ongoing changes in both, the society and the surrounding landscape. We can hear two women’s voices talk about a school that will be torn down and of a lake where out of respect one should remain silent. We get to learn about the magical power of plants and their alliance with anti-colonial resistance movements. We get to hear the groans of the hollowed earth in Malmberget echoed through a human body. And we also encounter monumental wooden sculptures, thematically related to the Sami mythology and inspired by figures from Sami ceremonial drums. In Luleå, in the former prison The White Dove we can take part in an enthralling singing performance and sound installation about the binding and healing power of the song, linked to factual tales embedded in the building’s history. At Luleå konsthall we encounter the story of an enigmatic illusionist and his decaying “magic-factory” in the outskirts of Jokkmokk that the earth is about to engulf. In the campus area of Luleå Technical University and near the magnificent rapids of Storforsen we experience sculptural forms made of birch bark that seem to be rupturing through the earth, bearing with them its many hidden stories. And last but not least, in an overwhelming dance performance, from its aseptic minimalistic beginning to the chaotic end, the merging bodies of women and plants become progressively wild, unpredictable, empowered and potentially dangerous.

By challenging the hegemonic ideology, these works open up towards other worldviews that seek the magic of the living earth in the everyday life and in ancient sources of knowledge. Altogether they point to the need to recover from our separation from the land as a way to repair our relations to each other.

Curated by Edi Muka in collaboration with Emily Fahlen, Asrin Haidari and Karin Bähler Laver

Producer: Malin Hüber och Olle Arbman

* Isabelle Stengers, Reclaiming Animism; e-flux journal #36 – july 2012

* Isabelle Stengers, Reclaiming Animism; e-flux journal #36 – july 2012

* Donna Haraway, Staying with the trouble