With the artistic intervention The Orchard of Resistance, Meriç Algün develops a complex and interwoven story in which transformation, renegotiation and conversion are central concepts. The tripartite work – installed in a monumental stairwell at the University of Gothenburg – expands, connects and creates a rhythmic movement with the starting point in the fascinating world of the fig tree.

Humanisten, the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Gothenburg, has been renovated and in connection with the rebuild artist Meriç Algün has created The Orchard of Resistance, a three-part artistic intervention, installed throughout the interior of the building, discreetly but distinctly contributing to its identity. The starting point and inspiration is the fig tree, its fruit and leaves. Through the artwork, its multifaceted symbolism and place in the ecosystem is given a direct relationship to the research and teaching that are conducted in the building, in fields including language, culture, history, literature and philosophy.

Curator text by Lotta Mossum

The Orchard of Resistance takes its starting point in the Galata district, an area of Istanbul where fig trees were cultivated in the 2nd century AD in what were then rural orchards. In 2014, in the present-day central city district of the mega city, the artist undertook a four-day systematic survey of today’s relatives of the fig tree. As a gatherer of facts and a woman, both foreigner and native, Meriç Algün discovered in the material she had compiled random social situations that exposed both patriarchal oppression and the displacement mechanisms of the urbanisation processes. In the work, various perspectives cross-fertilise and complement each other: the significance of the fig leaf in western art history, the etymology of the word ‘fig’, the interplay between certain fig species and an insect, the movement between the private and the public, the actual shape of the leaves and their shapelessness.

In the monumental stairwell that connects the five floors of the new Humanisten building, ten heavy, unique, life-size bronze leaves lie scattered as if they had floated down from the skylights. Together the leaves create a spatial rhythm in the monumental space. As a material, bronze is commonly associated with public sculptures, monuments, power and our desire for permanence. In the stairwell, however, Algün wishes to emphasise the covering function of the motif, the leaves. In western art history, fig leaves have often been used to conceal – and as a result draw attention to – that which is not intended to be seen. For example, for a period of time the naturalistically reproduced genitals on the replica of Michelangelo’s famous statue of David in the Victoria and Albert Museum were censored by a large fig leaf. In Algün’s intervention, the concealing aspect of the leaves is disturbed by its meticulous, sensual design that, in addition to being pleasing to the eye, also invites tactile intimacy.

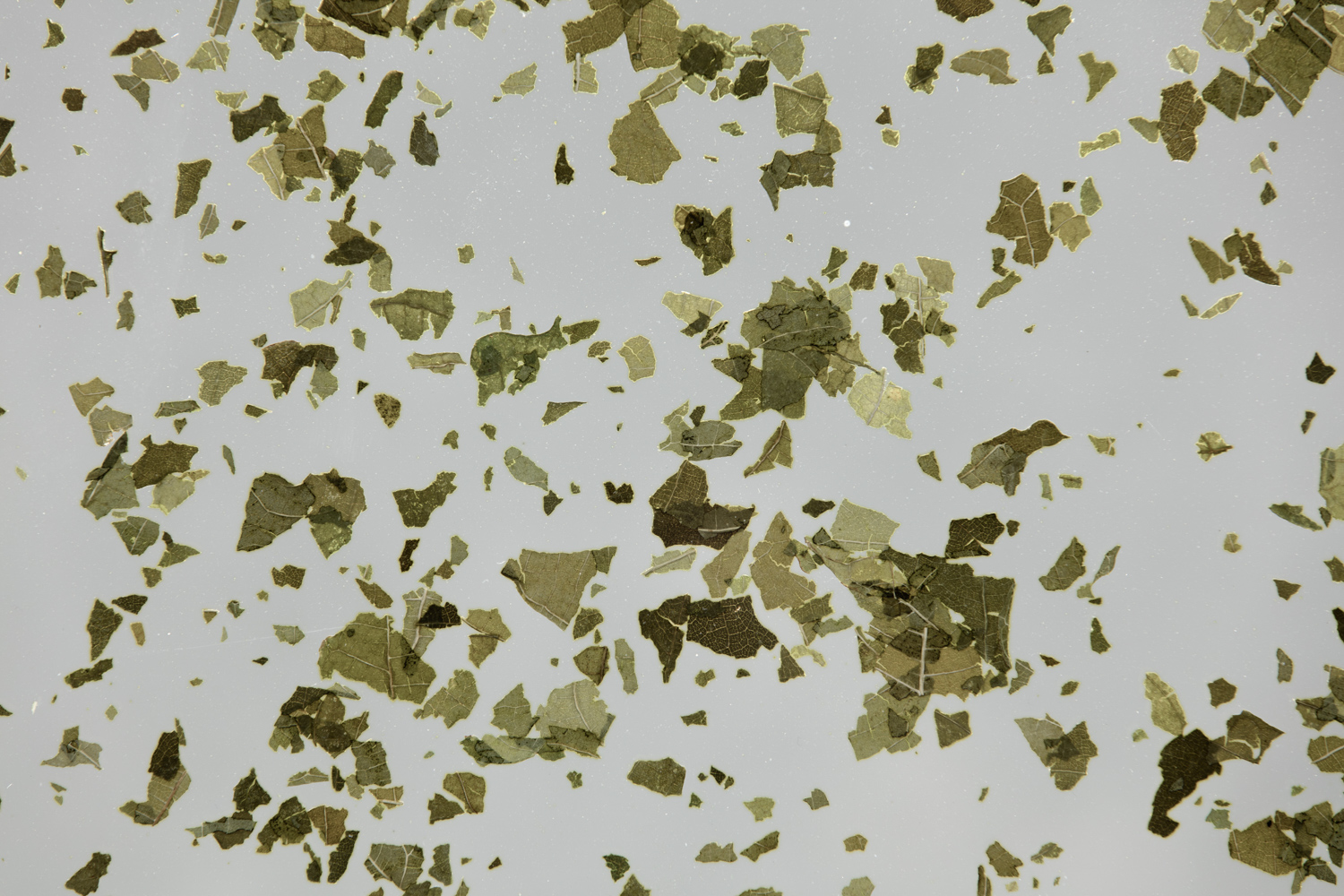

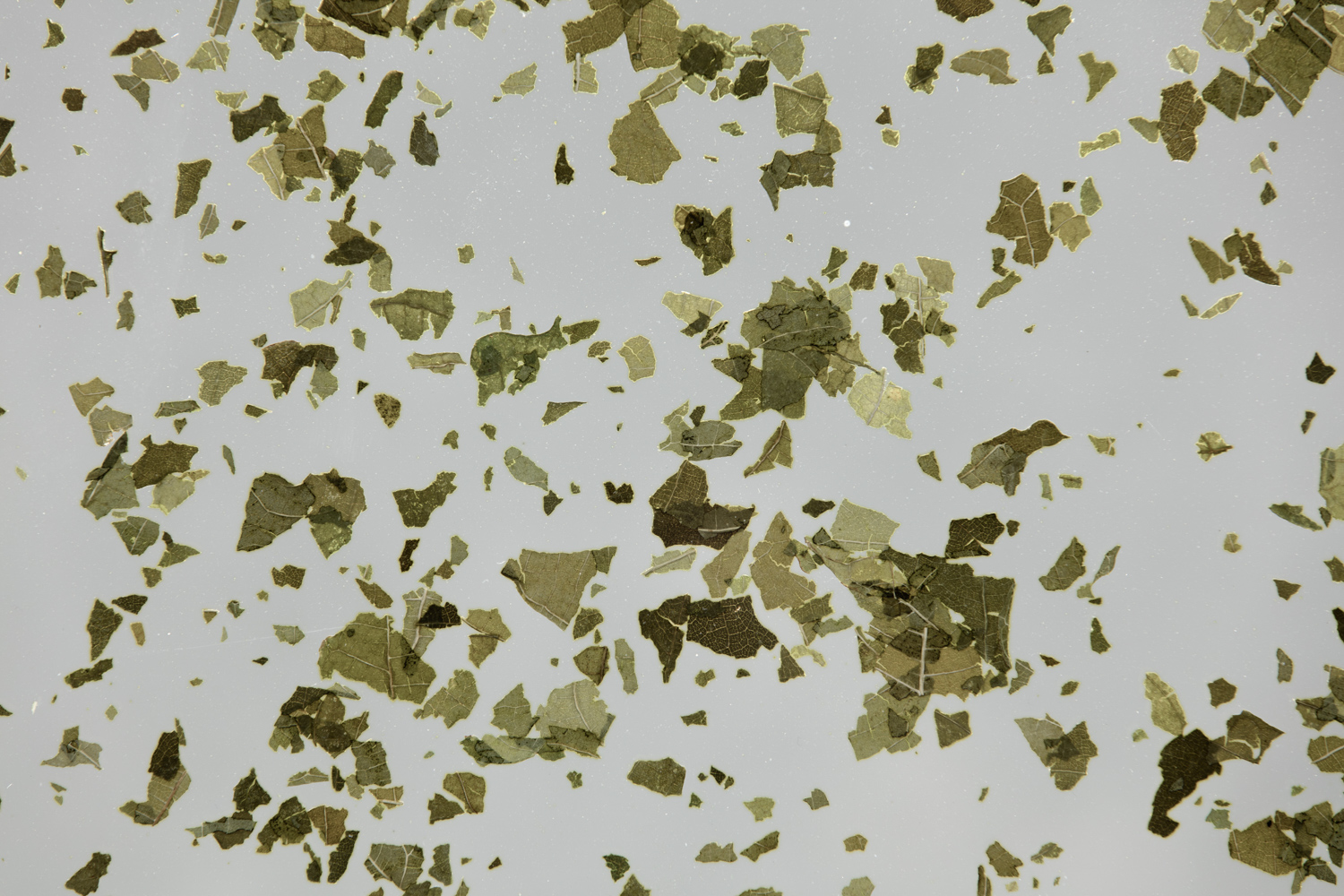

The glass walls surrounding the two group rooms adjacent to the indoor amphitheatre generate a dynamic between the binary opposites ‘permanent’ and ‘ephemeral’. Collected by the artist in her home city, Istanbul, the fig leaves have been allowed to dry before being crumbled into small fragments and laminated in the enclosing glass walls. The delicate, dried fig leaves contrast with the robust bronze. The fragments filter light, afford privacy and give rise to thoughts of fragility and transience. The artistic playfulness between paradoxes and dichotomies demonstrate a mutual dependence on linguistic binary opposites, where one pole helps to define the other. Revealing various linguistic layers, The Orchard of Resistance makes visible how language shapes our perception of reality as well as the malleability of language itself.

The third part of the work features a two-channel video installed in a quieter space on the ground floor of the building, adjacent to the theatre. The video work depicts an evocative fertilisation of sound, voice, narrative and visual material. We see the artist’s images from her survey of the Galata district in dialogue with film clips of the British zoologist David Attenborough describing an intricate interaction between a particular type of fig and an insect species that is specific to this fig – an interaction that has arisen during the evolution of the species’ respective reproduction cycles. Images of the insect’s gel-like body that presses itself through the opening of the fig fruit, of the fig’s soft, hairy, hard shell, of fruit juice that flows when hands pull the fruit apart, and of insects crawling out of the fruit are mixed with images of the Renaissance artist Masaccio’s painting The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, quotations by the philosopher Walter Benjamin and a rhythmic recitation of the etymology of the word ‘fig’. The word derives from Greek, Latin and Persian concepts for women’s genitals and female sexuality.

With The Orchard of Resistance, Algün develops a complex, interwoven narrative where transformation, renegotiation and conversion are central notions. The concept of central perspective is challenged as viewers are encouraged to understand the artwork by moving between its different parts and discover and incorporate experiences over time. In the western history of ideas, the concept of central perspective has structured our thinking since the 15th century. It is assumed that the viewing subject zooms in or out while observing an event from a fixed point. An idea of central perspective is that one can apply an approach to something that one is not a part of. This approach differs from the perception of space that can be found, for example, in Japanese gardens or in process-orientated painting and/or sculptural installations where a comprehensive representation is created through bodily movement. As here. View is added to view, one event to another without climax or culmination.

At Humanisten, bodies in motion echo Algün’s movements during her Istanbul survey. Through connections below and behind the stairwell the visitor can access the spatial corner where the two-channel video is installed. The video enhances the narrative on how knowledge and cognizance are passed down over time; orally, in writing and through images. This is how a multifaceted world emerges in a field of tension between elusive but controlling power structures and the driving forces of individuals to visualise and transform superiority and subordination. Facing the two screens in the video corner, comfortable armchairs provide visitors with the opportunity to reflect in private on issues of resistance and integrity raised by the artwork.

Lotta Mossum

On Meriç Algün

Born and raised in Istanbul, Meriç Algün currently lives and works in Stockholm. She has participated in numerous national and international exhibition contexts, including the show at the central pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale. Working in various artistic formats, Algün’s art deals often with identity and belonging that directly reflects her experience of movement across national borders, cultures, languages and bureaucracies.

Find the artwork

Göteborgs Universitet, Göteborg, Sverige