We met artist Anneè Olofsson for a discussion about her practice and the artwork Joint Custody, which was acquired for the Corona Collection, an initiative to support the Swedish art scene during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some descriptions stick more than others. Especially in the art world. “Realist”. “Romantic”. “Conceptual artist”. Words intending to sum up often multi-faceted, sprawling art practices. The most deceptive of these labels relate to a specific technique. Needless to say, artists who have devoted their entire careers to painting may, of course, be described as “painters”. Likewise, an exceedingly industrious bronze sculptor may be called a “sculptor”. But what about a “photo artist”

– who can be called that? Anneè Olofsson knows.

“I began working with photography in earnest in the early 2000s,” Anneè Olofsson says. “But I have never regarded myself as a ‘photo artist’. I have always worked three-dimensionally. That’s how I have constructed my photographic works. I don’t find artistic technique a particularly interesting topic. It’s all about what you see.”

Anneè Olofsson’s subject matter is often centred on her private sphere. She received attention early on for her images in which she appears with her father, mostly in pictorial spaces in which the figures come into view in sharp light, against a black backdrop. We are watching a situation, a connection that has been fixed in eternity, beyond time and space.

“It’s me and my parents, mostly my dad, that appear in the pictures,” Anneè Olofsson explains. “But it’s not about our private relationship; it’s about the bond between two people who are close to each other. A relationship that also changes over time.”

Sooner or later, the inevitable happens: one of the parties in the relationship passes away and everything changes. Anneè Olofsson’s father died in 2013. His physical presence is no longer there, but he exists in the form of all the objects he surrounded himself with.

The year after the loss of her father, Anneè Olofsson exhibited a sculpture that was touching in its simplicity: a black, folded-up beach chair. Unfolded, the chair exudes holidays, sun and levity. Here we encountered it in a crouched-down position, compressed, restrained by rough ropes. The work is bursting with energy – an energy encapsulated and bound, waiting to be released, brooding in its introverted state. The beach chair has its own history.

“It was the last object that remained when we emptied my father’s house,” Anneè Olofsson explains. “It wasn’t possible to unfold it; it had got stuck somehow. So I put it on the roof of my car and drove back to Stockholm. I think it has a kind of human appearance. It felt natural to entitle the exhibition in which it was included “Until Tomorrow Doesn’t Always Come”. When the people we love disappear, we lose a thread, but we pick up another one because the things they surrounded themselves with remain.”

Let’s return to Anneè Olofsson, the “photo artist”. She creates meticulously composed images that bring to mind the great masters of classic painting. Symmetries, sight lines, gazes and gestures are the result of a powerful artistic vision. Nothing is left to chance.

“From the beginning I was inspired by the great painters,” Anneè Olofsson says.

“Growing up, I used to browse my mother’s art history book. I agree with the old masters that one has to do things in the right way, technically speaking. But that’s not enough; there has to be space for the unexpected.”

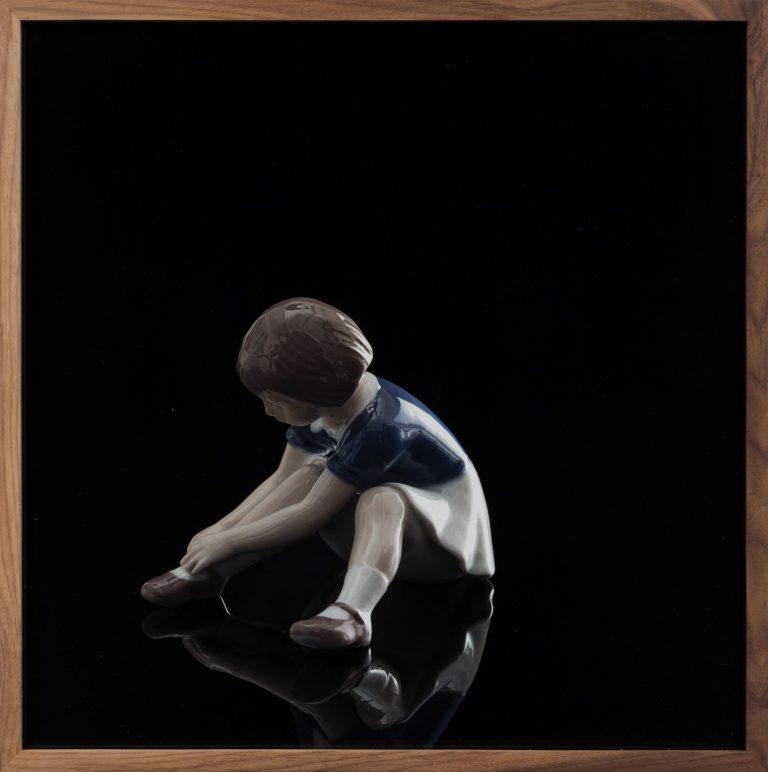

The unexpected in Anneè Olofsson’s art has often taken the form of minute details that are easily overlooked. She invites us into a visual world that seems familiar. But when we enter it, we realise that something is off. The point of departure for the artwork Joint Custody is a concrete phenomenon that we all can relate to: heirlooms.

“The work began with a group of figurines owned by my grandmother,” Anneè Olofsson tells us. “My father had inherited them and now they were mine. In fact, the title Joint Custody describes what it’s all about. I am the third-generation owner, but it feels like we own them together.”

Figurines have undertaken a breathtaking journey through art history. From having been regarded as fine art in earlier centuries they have been relegated to second-hand shops with a sadly low price tag.

“Figurines often represent children in the colours blue and white and I have always been struck by their melancholy character,” Anneè Olofsson says.

“They have an emotional, introverted trait that piques my curiosity. I used to make figurines, so the topic wasn’t alien to me.”

However, the topic did not provide a sufficiently strong source of inspiration for Anneè Olofsson. The figurines had to enter the photographic space in order to be liberated and find their own expressions. The series of photographed figurines feature a moment of uncertainty: one of the figurines has been replaced by a living child.

“It takes them out of history and into our contemporary age,” Anneè Olofsson claims. “We all live in an eternal bubble in which past and present co-exist. That people disappear and that our memory infuses life into objects is both natural and important. Time is significant; it changes how we see things and creates new contexts.”

Anders Olofsson

Coordinator, art applications, Public Art Agency Sweden

Artist biography Anneè Olofsson

Anneè Olofsson (b. 1966, Hässleholm) is a Swedish artist and photographer, educated at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts in 1990-1994.