Where are we? Somewhere in northern Germany, perhaps. It’s the middle of the day, anyway. Or possibly morning. The window is covered with raindrops. Now and then, a solitary drop trickles across the pane. A railway yard is glimpsed through the mist. And a bench, an empty, wet bench. A platform. Lingering, floating, an ashen landscape goes by as the train passes through an anonymous town somewhere in Europe. Then we travel through what appears to be another place, another continent. The sun is shining, the air is clear and the sky an electric blue. The architecture – tall, sand-coloured buildings with decorated facades – suggests North Africa. The Middle East? Cairo? Washing is hanging on lines outside the windows. Palm trees sway in the wind. The scene changes again. Outside the train we now see tropical, dense greenery. The air vibrates with humidity and heat. On the riverside, a group of people are standing, a man with a child on his arm waves before this image, too, disappears and we are passing through another place, a foreign city, a new coastline, a desert and a village, and then a city, over and over again.

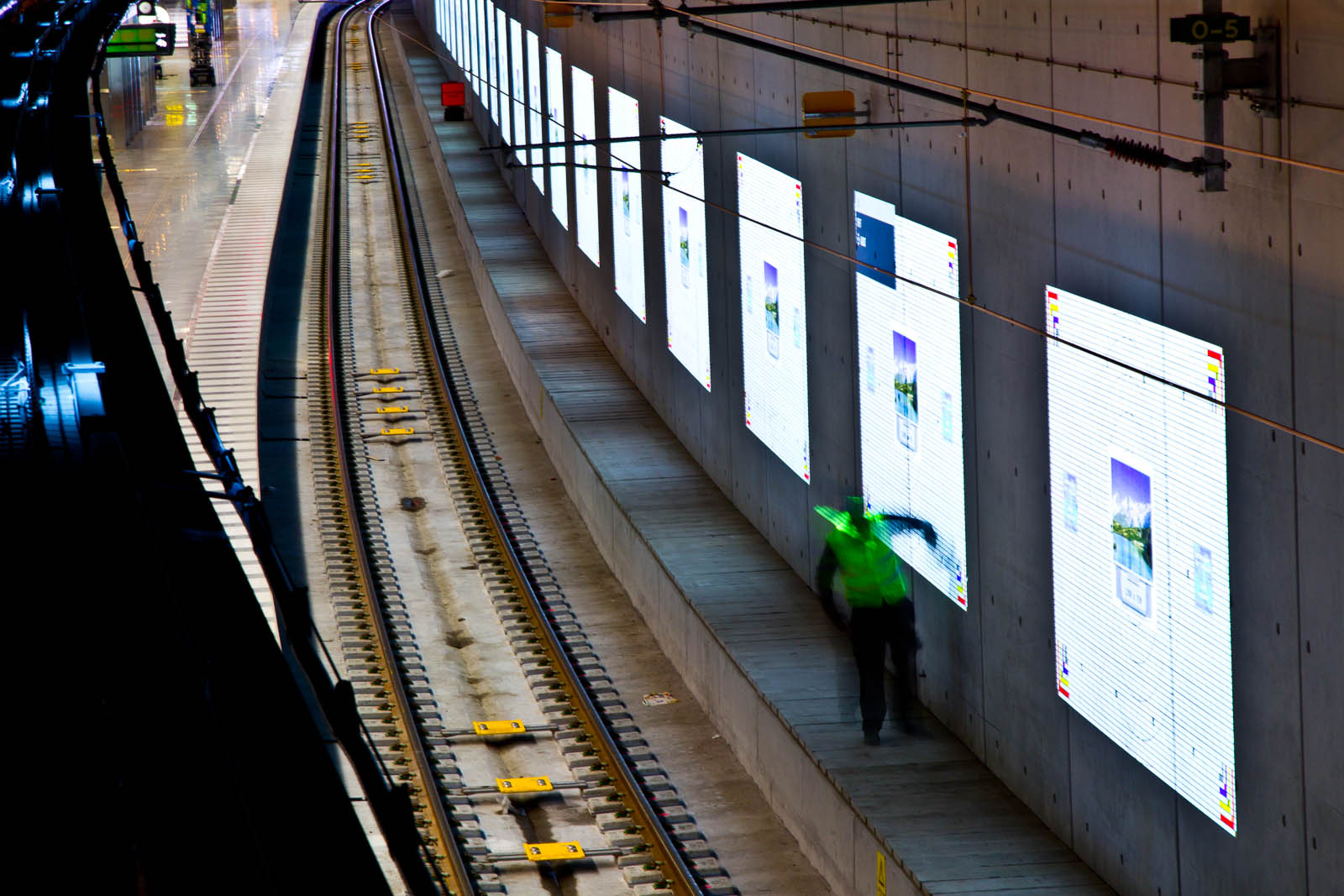

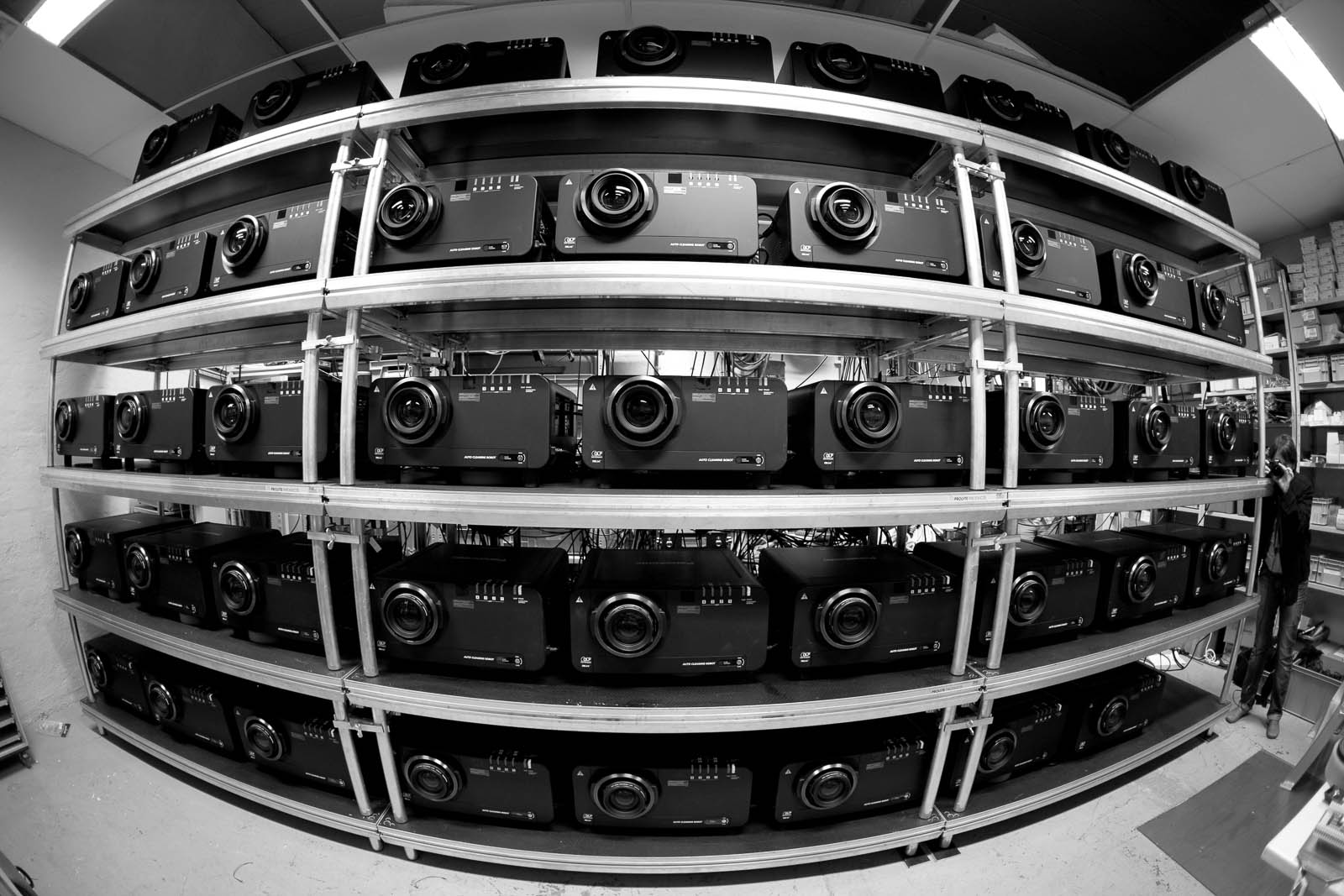

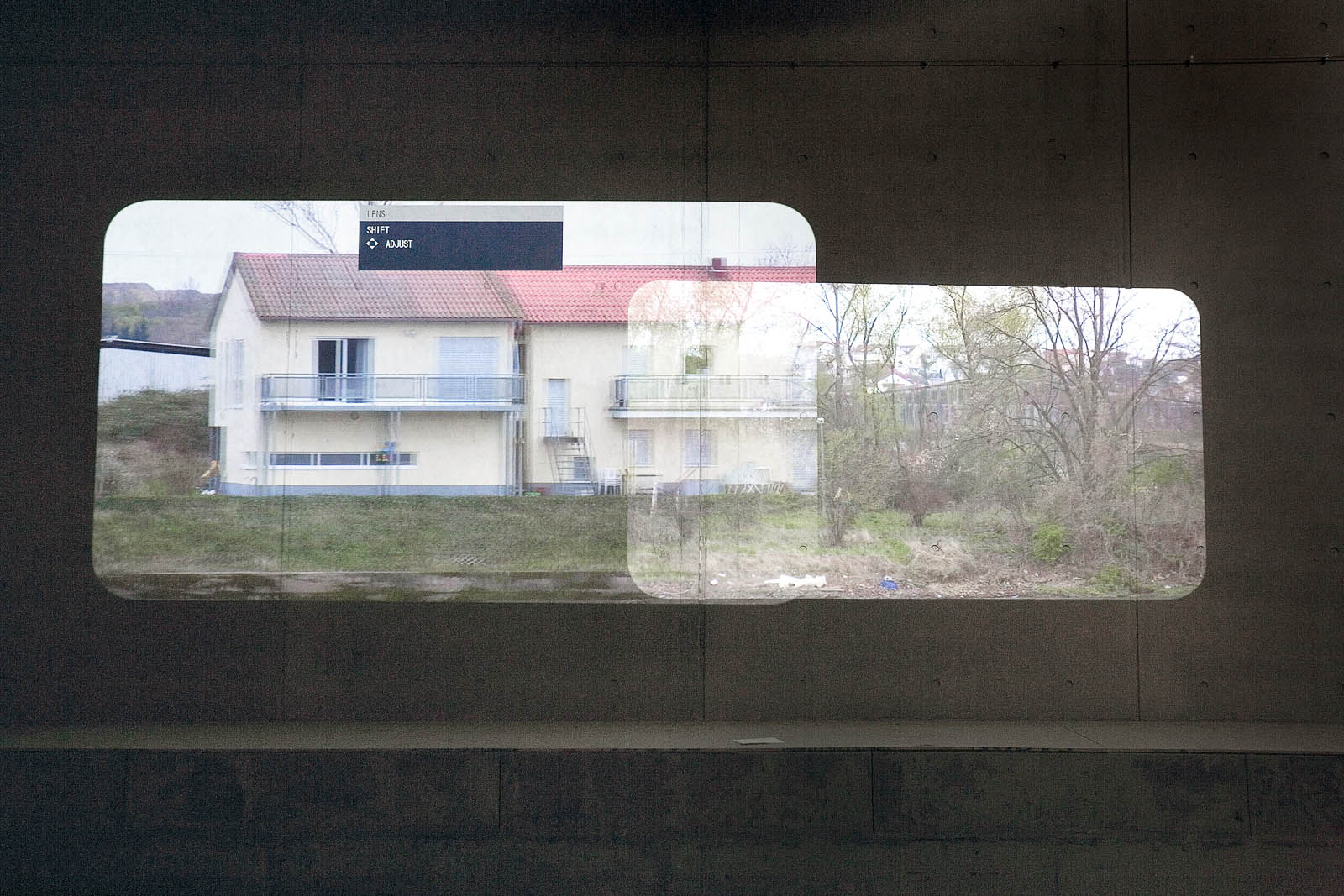

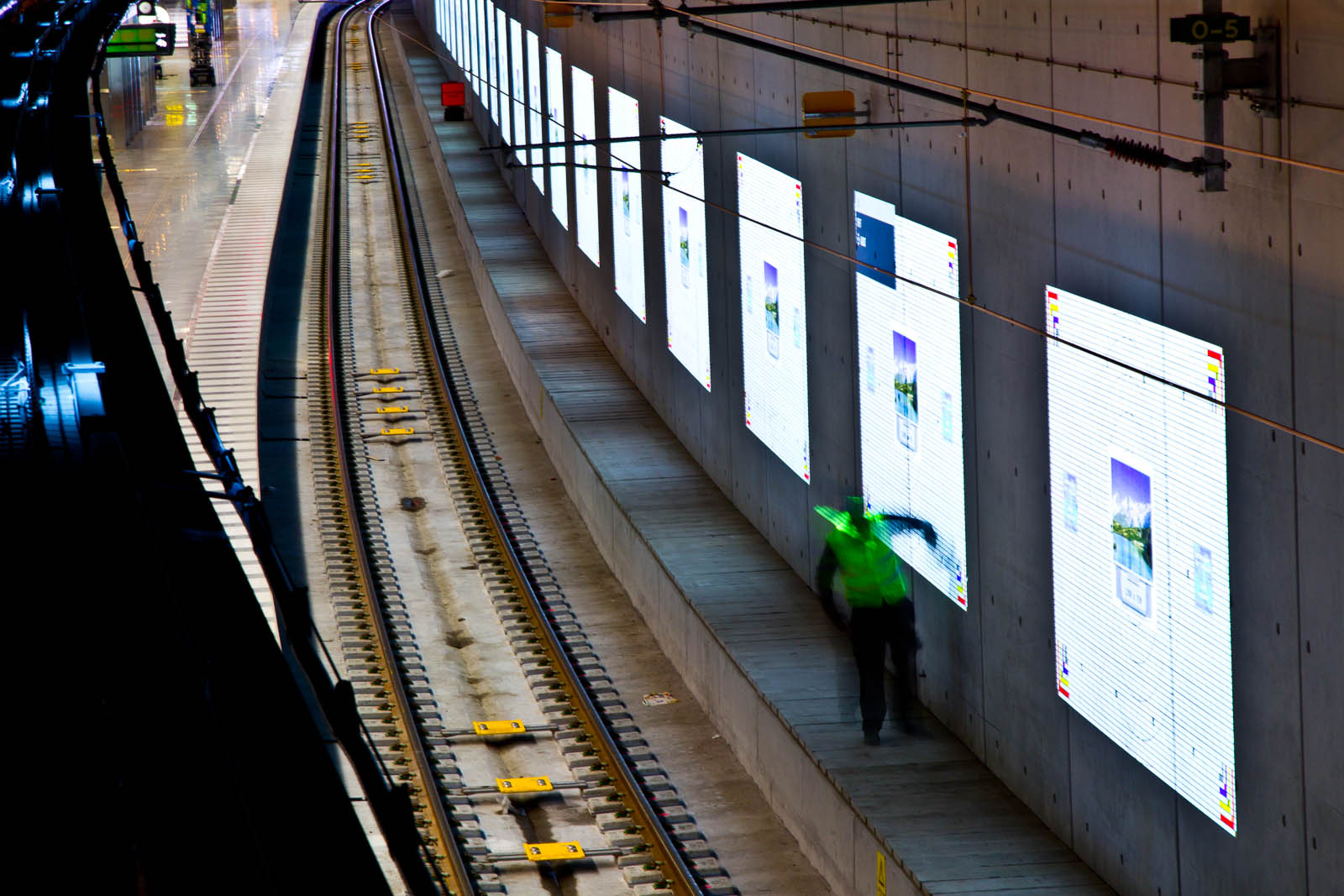

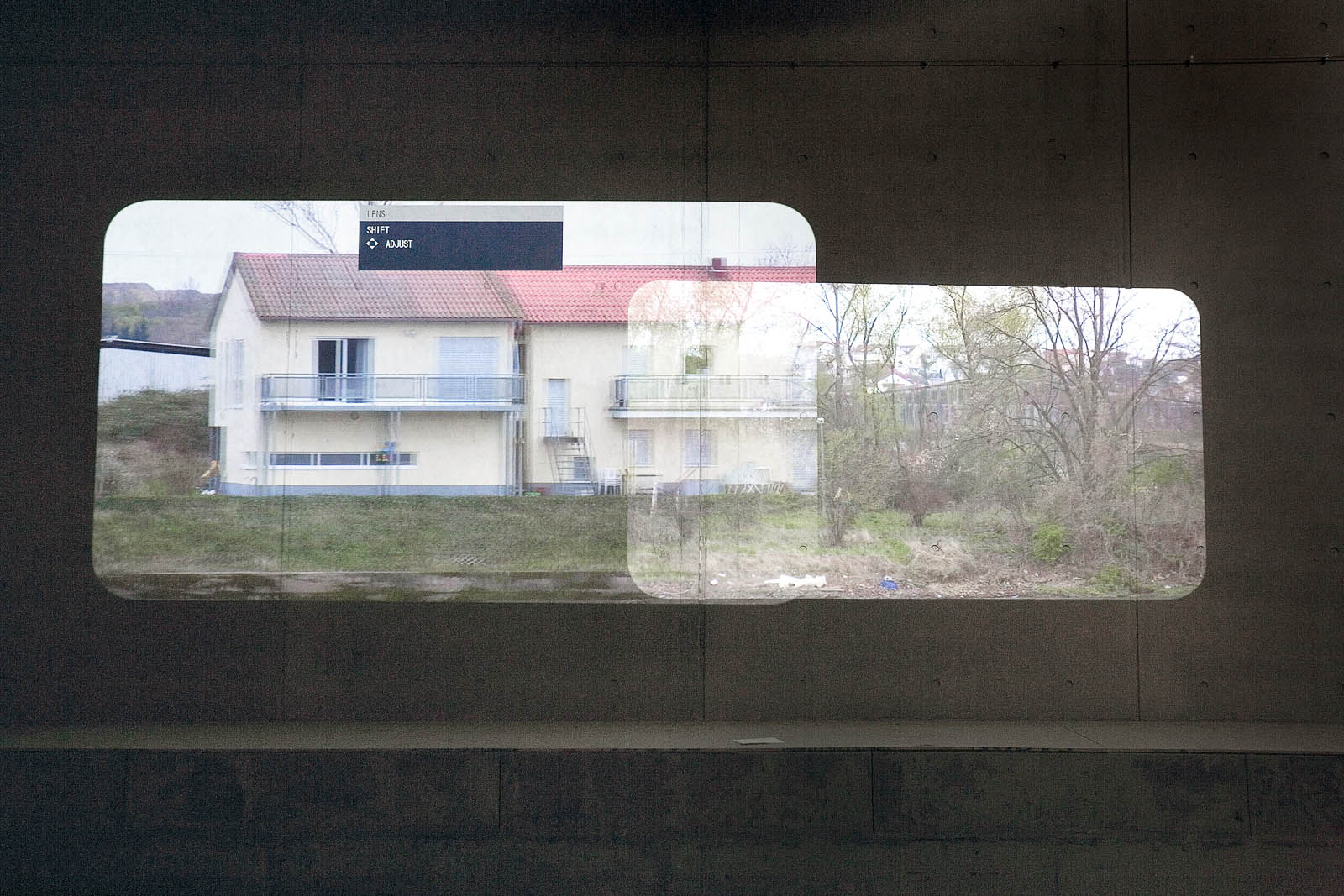

Tania Ruiz Gutiérrez has used a monumental video installation to transform the room at Malmö Central Station into the interior of an enormous train coach. Fourty-six large images in the shape of train windows are projected onto the north and south outer walls. A total of 1200 joined film sequences taken from boats, trains, buses, cars; vehicles generating a horizontal movement, hover and fill the surfaces. The illusion is so overpowering that we experience how the subterranean Malmö Central Station detaches itself and moves through the world, like an autonomous vessel. We could, of course, scrutinise the illusion and try to disassemble its various parts. The astute observer will discover a subtle yet distinct splice that regularly cuts through the train window/image. This happens when the film cuts from one sequence to the next. Moreover, the intensity of the colours makes the images look like animations, and the natural shakiness and vibrations of the voyage have been levelled out entirely. The images are projected directly on the concrete wall, giving a fresco-like texture to the surface.

The speed has been slowed down and synchronised – it is far too slow for a real train ride – to give the illusion of spatial continuity. The sequences segue into one another, and each projection is shown with a few seconds’ delay in relation to the previous sequence. They are intentionally programmed to be shown in a random order, so that daily commuters or regular travellers passing through Malmö Central Station will not experience the same journey twice. Many similarities can be found between trains and the moving image. Not only may a train compartment feel like and resemble a cinema, but in both these confined spaces we are passive observers, exposed to the passing images, unable to step up and influence reality. Films demonstrating modern inventions were extremely popular around the end of the 19th century. A show of moving, silent images of a spectacular technological novelty would make audiences flock to the cinemas.

The images are projected directly on the concrete wall, giving a fresco-like texture to the surface.

Films about the increasingly efficient transportation methods – especially trains – were an infallibly popular theme. Journeys on the newly-built New York City subway were, for instance, a subject that was often documented on film, and “Train-rushing-at-ya” films were a special, and much-loved, genre in its own right – passenger trains were filmed from the front by an immobile camera as they pulled into the railway yard or station. One such early film is the Lumière brothers’ L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat from 1895, shot in one 50-second take, showing a steam engine approaching the platform in a small town on the French coast. The train comes at full speed towards the audience. Legend has it that the whole auditorium panicked at the première in January 1896. Historically within engineering, and phenomenologically, there are other strong links between trains and film. The use of trains is believed to have led to changes in seeing, to a new visual perception of the world. One example of the first attempts to generate mechanical, moving images is the animated panoramas that simulated fantastic voyages by train or ship: immense paintings were rolled out before the audience in sections, to the accompaniment of a dramatic narrator’s voice. This innovation coincided with the breakthrough of public steam railways in the 1820s.

The work Elsewhere shows a train journey without beginning or end. It’s not where we are that is important. The essential thing is the experience of travelling and watching the images go by. Yet, we persistently try to orient ourselves in time and space. We are forever searching for symbols, signals or signposts that could reveal or give us a hint about where we are and a valid geographical position. This installation is about the phenomenon of travel. Early in life, we learn where our own body ends and the world begins. We also soon realise that we can move from one place to another on our own, even if it is just across the floor, to experience new things. Being born and dying in the same place on earth used to be the norm a few hundred years ago. The world that was unknown. It took months to cross the ocean, days to travel across a country.

The world is experienced as being smaller and closer. Similarly, we have more options and places to visit than ever before – travelling long distances for the maximum sensory experience is sometimes regarded as a human right and a perfectly natural thing.

Nowadays, there are few places in the world that have not been mapped. We travel between continents and time zones in a matter of hours. We can even traverse the globe digitally in a matter of seconds. Information, experiences and relationships hover around us in the atmosphere, constantly at our command. It has been said that modern progress, with its increasingly rapid transport and communications has shrunk both time and space. The world is experienced as being smaller and closer. Similarly, we have more options and places to visit than ever before – travelling long distances for the maximum sensory experience is sometimes regarded as a human right and a perfectly natural thing. Given the will and the financial means, contemporary man can lead a hypermobile life, working and living alternately in different parts of the world. The notion of the perfect voyage, where we leave our arduous everyday life behind, is just a fantasy.

Yet, it is something we all dream about, having been fed with images of exotic beaches, panoramas, landscapes, and smiling, contented people who seem to have no problems in their lives. None of the exasperations of a long journey are shown in these images. Another demanding aspect of the global reality is involuntary travel and flight from warzones and nations in crisis towards an uncertain future. Our journey at Malmö Central Station is an optical illusion. We, the passengers, are not inconvenienced by the changes in time or culture, and there are no tickets or passports or checkpoints on the way. The digital fantasy world on the station walls is seductive but artificial. The work Elsewhere appears to say that a railway station is not just a place where we must wait passively for what will take place somewhere else, in the future, in another part of the world. The work claims that a perfectly ordinary station can be magical, with a reality worth experiencing if we are present, mindful of the here and now. Perhaps we could even experience the most remarkable things just by standing perfectly still on the platform, without moving at all?

Karin Faxén

Work In Progress

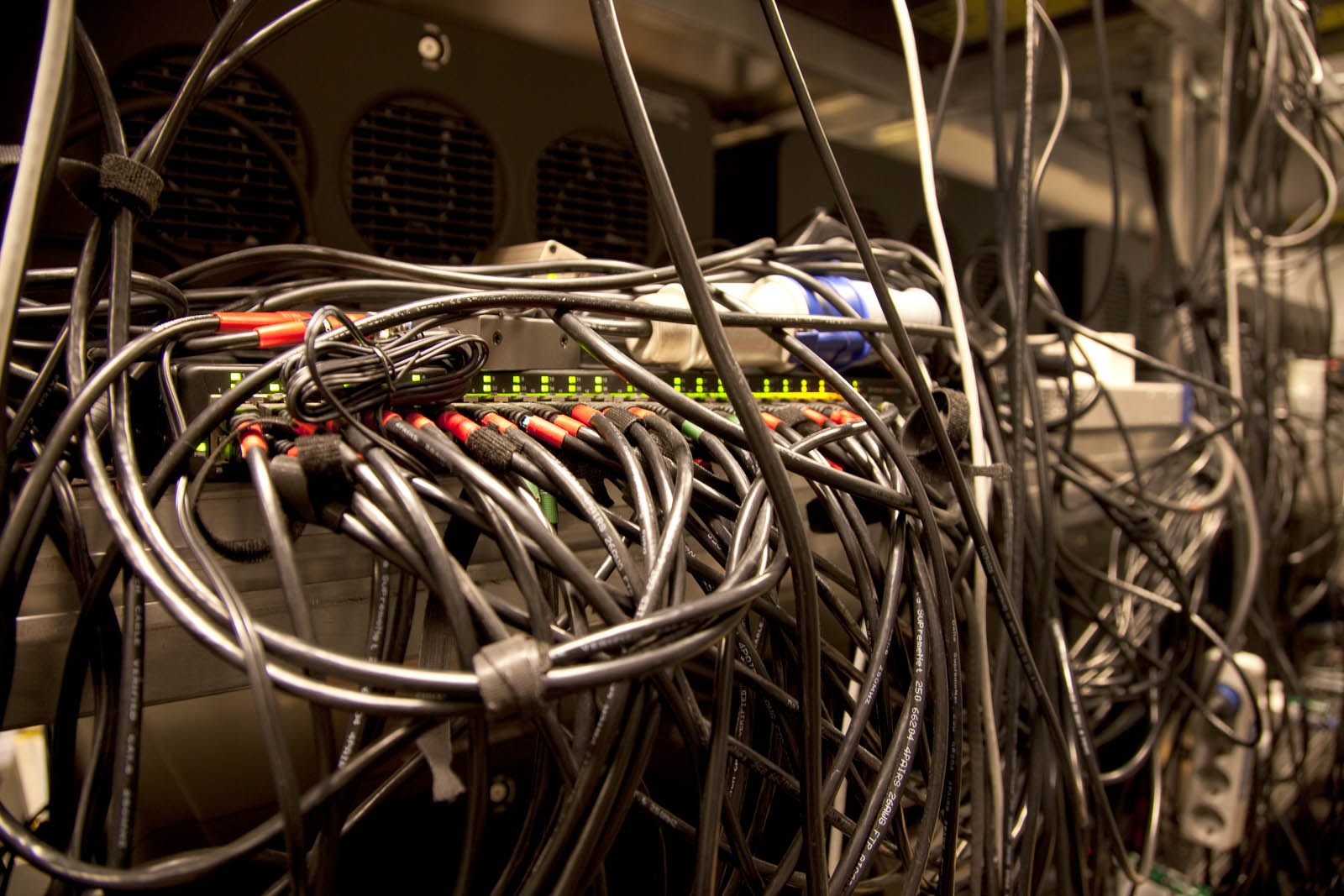

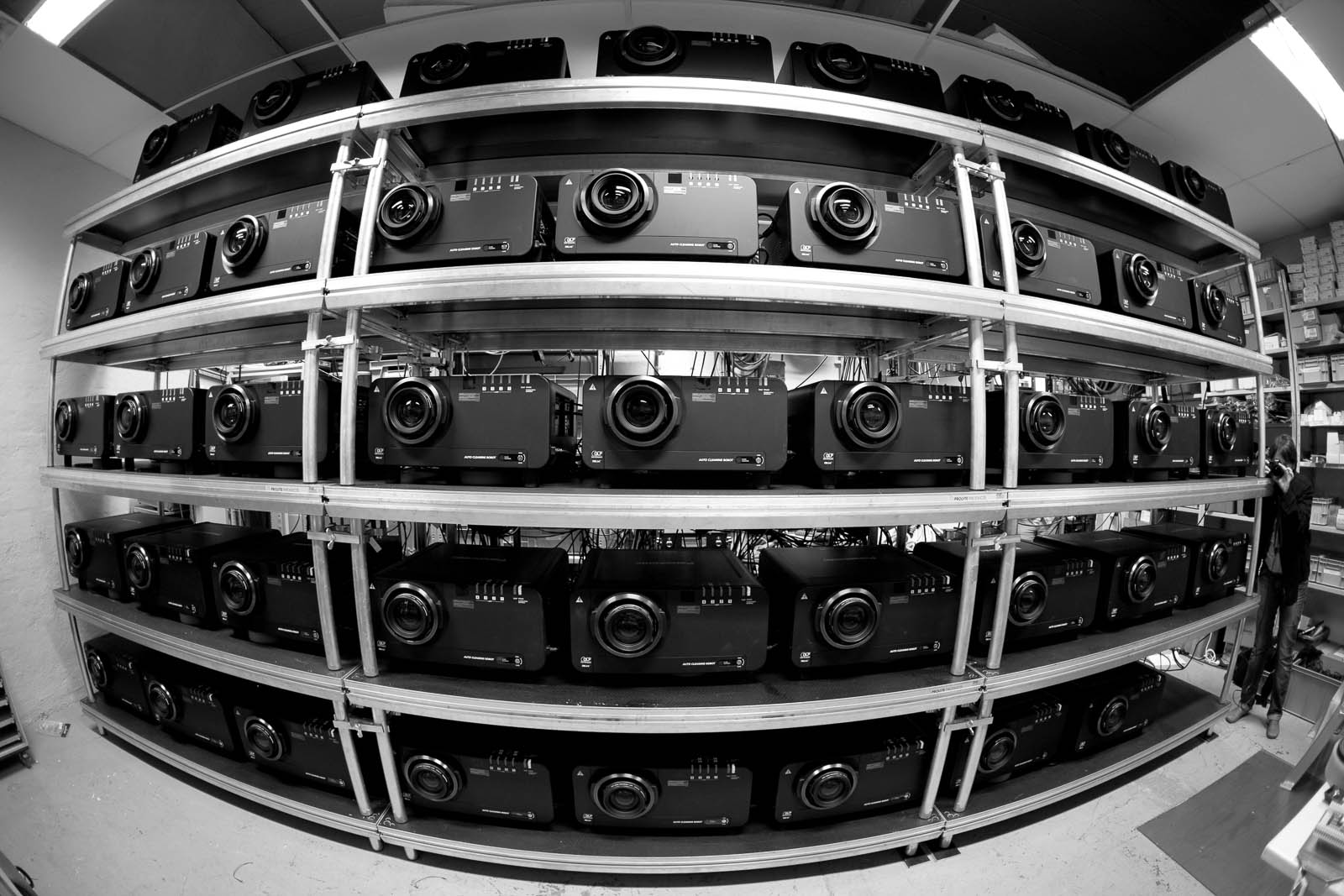

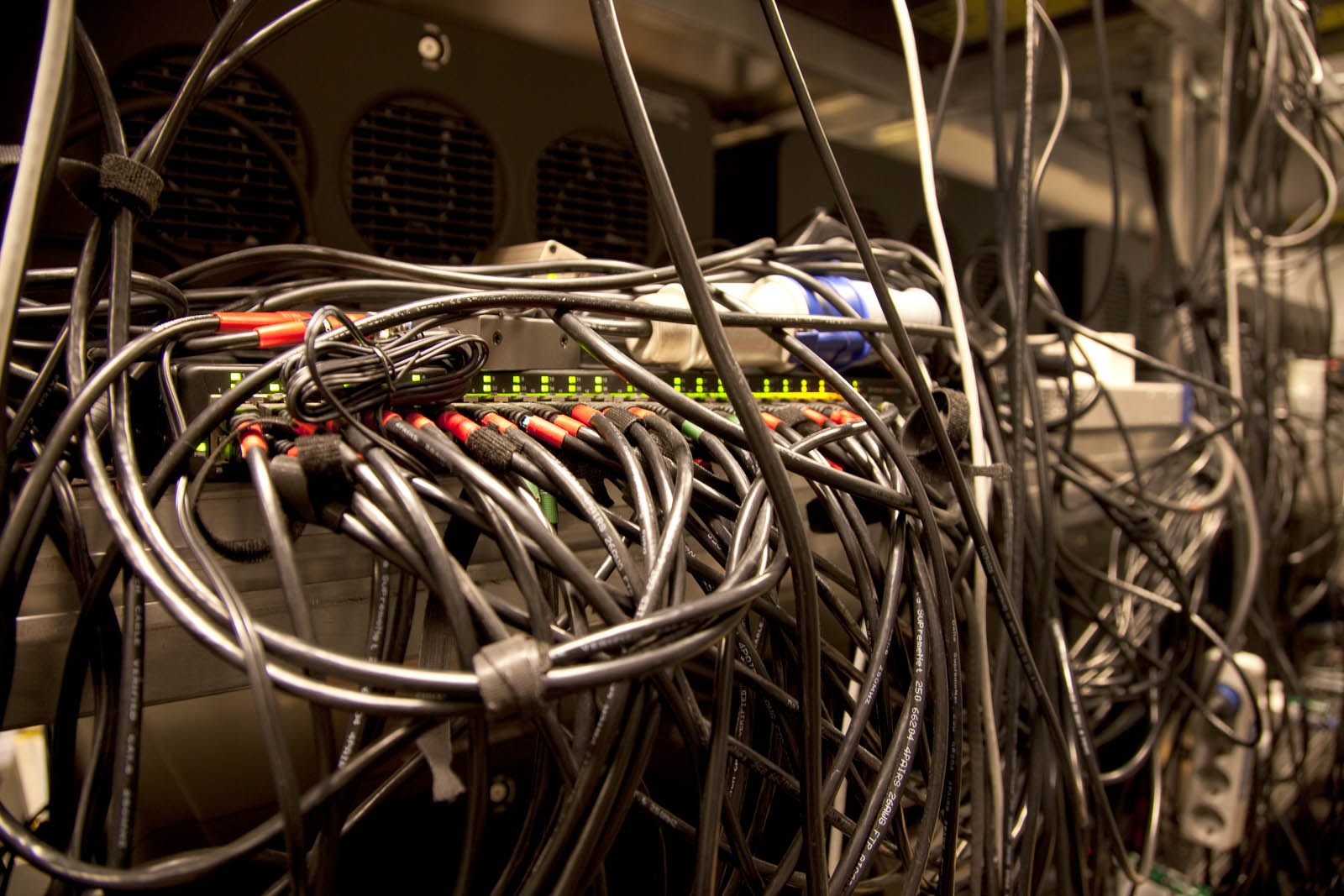

Elsewhere is coming to life. Tania Ruiz Gutiérrez’s video artwork while it is tested and installed.

Find the artwork

Malmö Centralstation

Skeppsbron 1, 211 20 Malmö