Faced with work by Charlotte Gyllenhammar (b. 1963) it is difficult to remain a passive observer. As soon as one begins to look a little closer at her works, they twist and turn and draw the beholder ever deeper into a world in which what one thought one saw is changed into something different. I don’t know anyone else who can make something familiar feel strange to the same extent as Charlotte Gyllenhammar, and vice versa. Her art has a capacity for getting under the skin of the beholder.

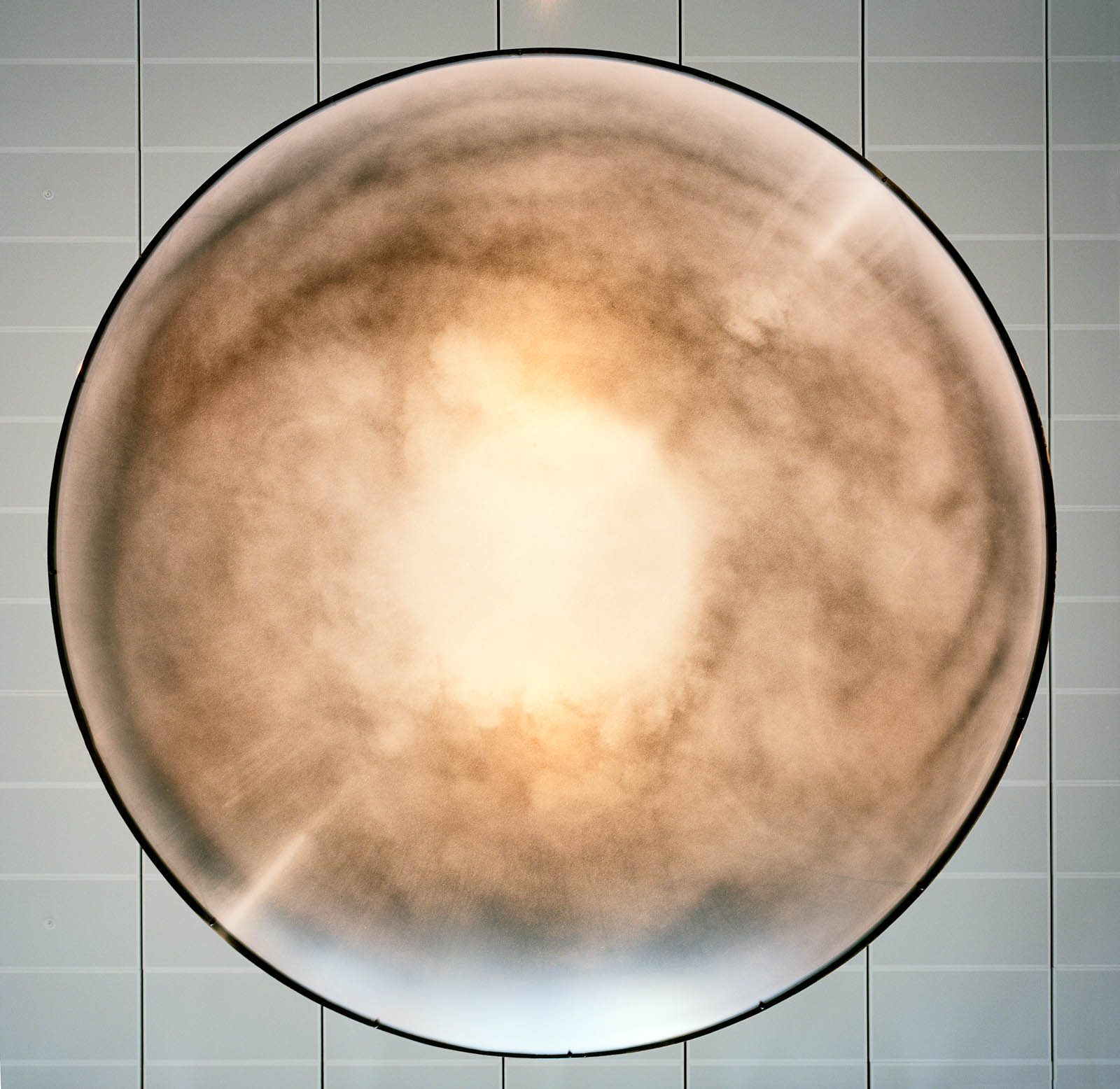

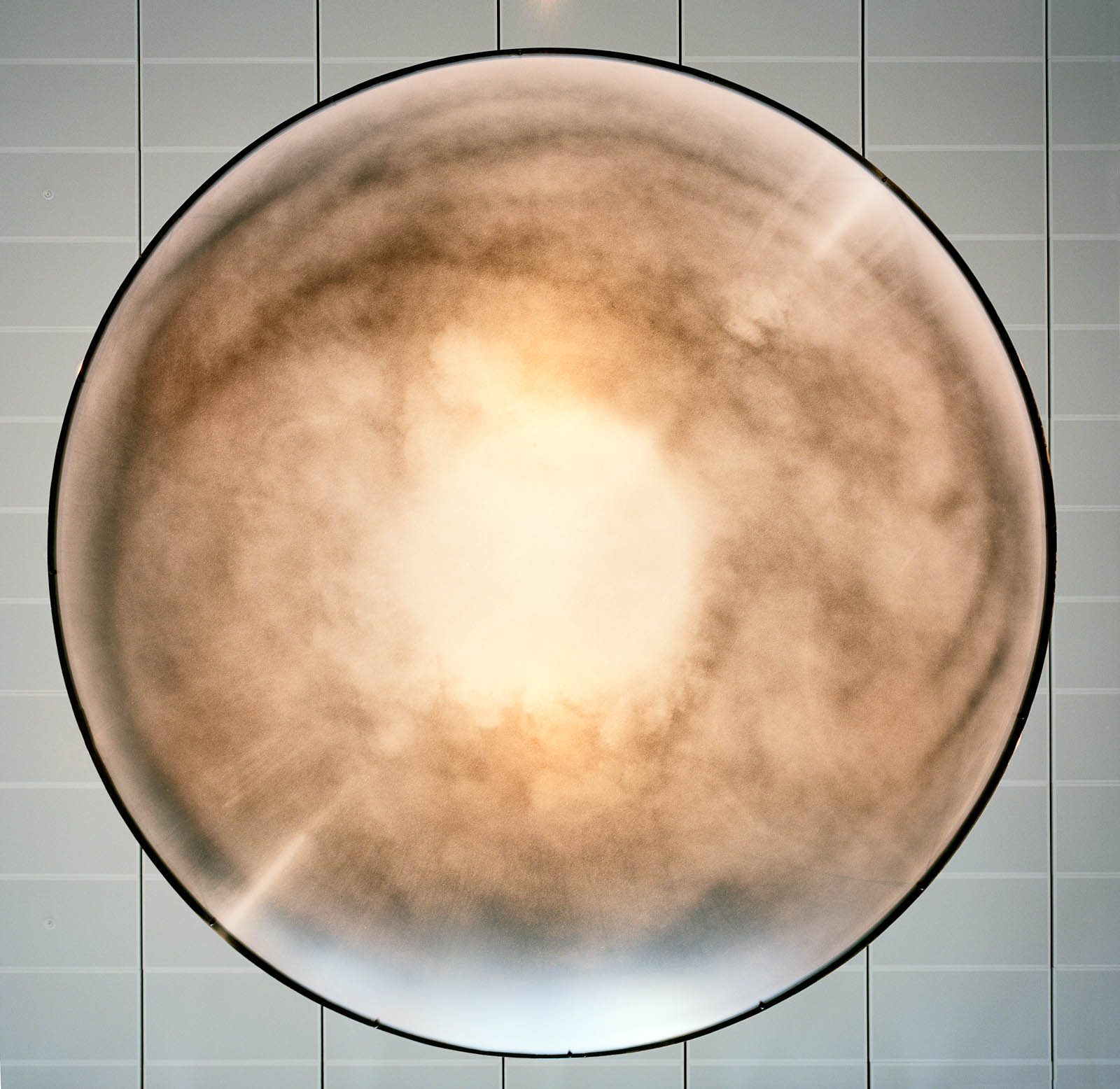

Her installation in the joint entrance hall of the Swedish National Defence College and the Swedish Institute of International Affairs is a good example of this. A black and white photograph of a dramatic cloud formation that seems to open itself above a group of children sitting directly beneath it can be seen in the large, hovering cupola. But what does this portend? Is it a covering of clouds that is breaking up or is it a threatening explosion? Or is it, perhaps, an all-seeing eye? And in that case is it an instrument of surveillance or of protection?

The more one looks at the work, the more uncertain about it one becomes. It is like a game in which the work attracts one by its clarity only to reveal its diversity.

None of the children under the cupola is particularly active; one of them is kneeling and looking up into the cupola but the others do not seem interested in it. When one looks more closely at the children, several strange features appear. They are all differently dressed. One child is bare above the waist, another is wearing more clothes as though for playing outside. The kneeling child is wearing a jacket with a hood but seems to have nothing on below the waist. The clothes are depicted in detail and seem to be casts of real clothes but the children themselves are more or less coarsely modelled; one of them has hardly any facial features. Are they melting in their clothes? Are they wasting away or are they still not finished?

The more one looks at the work, the more uncertain about it one becomes. It is like a game in which the work attracts one by its clarity only to reveal its diversity. The more one is drawn into the game, the more one is faced with one’s own attitudes. A cat and mouse game which is the image of all truths: the more that we consider them the more questionable they become.

The amalgamation of different perspectives recurs throughout Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s work. What is public is also private and vice versa. When she is dealing with grand subjects such as terrorism or political events that affect the whole world, she does this in the light of her own experience. As early as her exhibition entitled “Sprangning” [Explosion] in 1991 she asked questions about the threat of terrorism, taking as her starting point a travelling case that had been blown up. The contents of the case were spread across the floor of the gallery while negative reliefs of a female body hung on the walls. But was the woman a victim or the perpetrator of a crime? The work reflected the threat scenario that was spread around after the Gulf War and the woman could readily be seen as a proxy of the artist herself.

In Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s work the threat scenario is rapidly shifted to a personal level where clear answers are lacking and the official explanations and statistics become rhetoric. At the same time, her point does not lie in contrasting things with each other. Rather, she directs her attention to certain intersections where, for example, what is private becomes public and the other way round. The way in which she makes use of the media is an obvious example. Her exhibition “Hinder och forkladnader” [Hurdles and disguises] (2003) dealt with the TV broadcasts from the hostage drama at the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972. The TV news footage becomes a part of the public domain lowered into the private sphere where public pronouncements are transformed into private memories. Charlotte Gyllenhammar has also let private matters become public, not least in the works that use her studio as their point of departure. In Wanås sculpture park she buried an exact replica of her studio upside down in the earth. Here the private sphere is literally sunk into the public domain.

The tension between public and non-public recurs in the installation at the Swedish National Defence College and the Swedish Institute of lnternational Affairs. This is a public work in a public venue. But the building is not as public as a city square. It is not a place that people visit unless they have some errand there. The fact that the installation is in the entrance hall makes this all the more evident. The visitor is not really inside the building but is definitely no longer outside it.

Charlotte Gyllenhammar makes use of the duality of the entrance hall, its position between outside and inside, by dividing her installation into two parts. When the visitor registers at the reception desk she or he becomes aware of the second part of the installation. Behind a window that looks out onto a courtyard there is a sculpture consisting of two children. One of the children is standing very close to the window staring in while the other child is sitting in a toboggan on a little hill casually waiting for the snow. The standing child is warmly clothed, wearing a winter overall with a hood and gloves. Perhaps the children are prepared for more than merely snow.

Gazes that lead into a picture or sculpture deceive the beholder into entering an illusory world but gazes which look out at the beholder break the illusion.

The beholder is caught here in a play between different gazes. The “eye” of the cupola guards the children in the inside group. The children, in turn, either “look” back at the cupola or appear not to care at all. They seem to be busy with their own thoughts. At the same time, the children who are on the outside look actively into the room and back at the beholder. They seem to be most interested in what is inside.

The direction in which people are looking is fundamental to how we read pictures and sculptures. By following their gazes we become aware of the hierarchical structures of the world that the sculpture depicts. Put simply, the person whom everyone is looking at is the most important one. As early as the renaissance, painters created works in which someone is looking directly at the beholder of the painting. Usually this is a feature of a self-portrait as though the artist wants to see us looking at what he or she has done. But there are also paintings in which the characters turn their backs on the beholder and look in at the painting themselves. These figures play the role of proxies. When we look at someone’s neck, our vision is shifted so that we see through that person’s eyes. The Ruckenperspektive was much used by 19th century romantics like Caspar David Friedrich but was also regularly employed by Alfred Hitchcock and is now used in “first person” computer games so that the player can identify with his or her avatar.

Gazes that lead into a picture or sculpture deceive the beholder into entering an illusory world but gazes which look out at the beholder break the illusion. Thus the direction of the gaze is a matter of types of consciousness. By means of a proxy we can enter the world of illusions and can immerse ourselves in what Laura Mulvey-feminist film theorist-calls visual pleasure. Within the illusion we can indulge in things that we otherwise would not do. But the moment that we become aware of the fact that We are the beholder, the illusion is broken. And nothing so rapidly makes us aware of ourselves as when we discover that someone is looking at us. In fact it is only at that moment, Jean Paul Sartre opined, that we start to reflect on what we are doing; looking through the keyhole is not the problem. It is only when we are caught looking that we are embarrassed. Hence his conclusion that hell is other people.

In Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s installation the beholder is caught in a field of tension set up by the directions in which the figures are looking. The visual pleasure, the desire to immerse oneself in the world that the work of art creates, is opposed by the fact that the beholder is also beheld. Thanks to this interplay, the installation shows us that the public aspect is a matter of belonging; and who belongs is a complex issue. It is a matter of who is outside and who is inside but also of what is due to the person who belongs to a certain space. If you belong here, do you then have some sort of responsibility for what is going on outside?

The public domain has always been a stage for affirmation. It is here that we display ourselves as we wish to be seen. But Gyllenhammar reminds us that there are other gazes too; others to take notice of than just those to whom we choose to show ourselves. The child outside the window looks in with a demanding gaze. You won’t forget me, will you?

Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s installation refuses to be “merely” ornamental. It poses questions to the beholder that make enormous demands regarding responsibility and participation. But it achieves this without lecturing or exhorting. The anonymous children bring the issues down to a personal and domestic level. The consequences of geo-politics are felt on the level of the individual. Thoughts about affiliation and threat scenarios are paired with her intimate modelling and fine details. She directs the room and lets the beholder go from one perspective to another without giving greater weight to either of them.

Charlotte Gyllenhammar is looking for the state at which both poles are present. One might argue that she works either at dusk or at dawn. In the borderland between day and night, what is to come is portended. Nothing is ever as poetic or as threatening. Perhaps the world is at its most beautiful as the light fades. But it is then, too, that the phantoms appear.

Håkan Nilsson

Find the artwork

Försvarshögskolan, Stockholm, Sommaren 2006

Drottning Kristinas väg 37, 114 28 Stockholm, Sverige