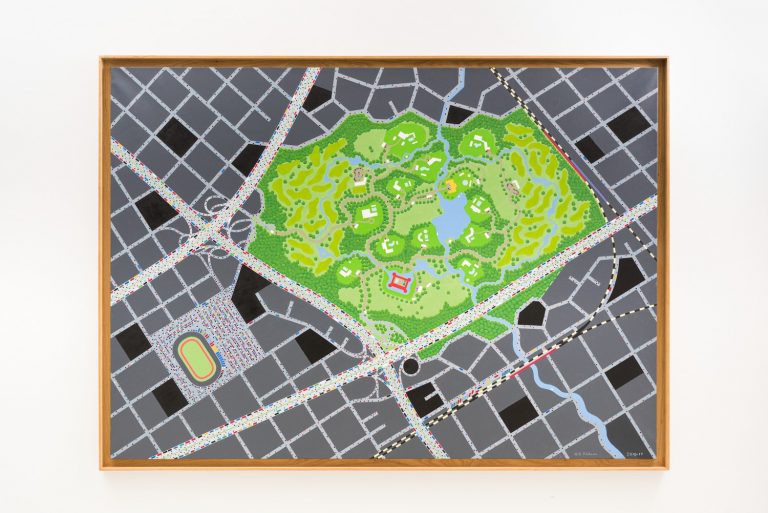

Death by Nature is a wall installation composed of lug wrenches, a Volvo grille and nails. It was acquired for the Corona Collection, an initiative to support the Swedish art scene during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The installation Death by Nature is mounted on a wall in a form reminiscent of a smiley. This is how the artist describes the work in the interview with Power Ekroth, in conjunction with an exhibition at Contemporary Art Stavanger:

”I will also bring a “Swedish death”, in the form of a Volvo emblem. Volvo is no longer present where I live now, so it’s about a sort of balance and about pointing to something that was a fixture for many years and no longer is so. Death by Nature, so to speak.”

Klas Eriksson works in a number of techniques, including photography, painting, performance, video, sculpture and installation. He is interested in issues related to control, power and limitation.

Klas Eriksson in Conversation with Power Ekroth

Klas Eriksson works in such a way that ordinary relationships are called into question. It may be relationships relating to social power structures, the art world, economic conditions or communities. Eriksson introduces dislocations that initially may appear insignificant but rapidly gains in importance as his work often succeeds in hitting a nerve. For the exhibition at Prosjektrom Normanns in Stavanger, it felt wrong to write a standard exhibition text; it would not have been fair to the viewers or to the artist, partly because the exhibition is composed of multiple layers of meaning and partly because a text about Klas Eriksson, in the end, of course, would have been hijacked by himself. Instead, we decided to have a conversation.

This is our third collaboration. First I invited you to participate in a group exhibition at Skien, Telemark Kunstnersenter (TKS) in the beginning of 2014, which caused a great stir. Then you invited me to edit the fourth issue of your fanzine Reptilhjärnan and in conjunction with this I asked you to produce a solo exhibition at Prosjektrom Normanns, Stavanger. Issue number five of Reptilhjärnan will be edited by yourself, and you have explained that it will mark the end of your fanzine. Why did you start it and why are you now ending it?

It began as a kind of reaction towards an exhibition text that had to be written. I didn’t like the idea of engaging someone to write about my work, pay them with money from the budget and end up with an A4 about one’s practice written by someone else. Instead I imagined some kind of exchange, and perhaps also a time out, in some way. A shift where the artist chooses a curator/art critic to write about my work based on a given theme. In this way, I will curate my description. Instead of having a curator contact me based on their agenda, I contact a curator based on my own agenda.

I invited you, Power, to edit the “Art and Institution” issue, on the basis of one of my experiences as an artist with an institution. With Reptilhjärnan, I wanted to challenge the idea of art and text, in the format of a fanzine. I invite artist colleagues that I think suit the given theme. I produce the graphic design, including images etc, and the editor produces the text. The final issue, which will be released on 24 May, will have the theme “Art is Artist” and I will be the editor because I am an artist. All the issues have been printed with support from different institutions, in editions of 100 copies. I like to restrict some parts of my art practice, which is why I will only do five issues of the fanzine and never again return to it. I’m speechless with admiration for all the contributions and it’s been a blast.

Issue number four of Reptilhjärnan, entitled “The Norway Issue”, contains cuttings from local papers in Skien, including a comment from Torbjørn Røe Isaksen, the Norwegian Minister of Education and Research. Why do you think people were so enraged at your 2014 work LOLERZ (+ +)?

Yes, well, I was discussing this as recently as today, but I can’t figure out why it created such a hullabaloo. I think a lot about prejudices as a kind of quality that sprang from this work. In order to have a prejudice, you have to – at least to some extent – have the hots for that which you have a prejudice about. It’s a very sweet thought. I think that many people, including the minister, were challenged by the work and now think about contemporary art more than they did before. Torbjørn may even understand that he has a prejudice and that he perhaps is a little bit in love. The work was performed with all necessary permissions and it was temporary. It is now gone forever (the building is even cleaner than it was before). On the back of these facts, it’s almost absurd to think of the immensity of the reactions. Looking back at it, I think I tried to approach Norway as a nation, with my prejudices about money, budgets and artistic conditions.

I was happy and stoked about the permissions and so on when I executed the painting, and I’m not angry or pissed off at all. For me, the work was important for a number of reasons. Firstly, from the point of view of some of the aspects related to the financial conditions of cultural workers; secondly, from the point of view of me approaching Norwegian culture as a Swedish artist and, finally, I also wanted to shed light on the fact that the building is now a cultural centre and no longer a bank. It turned out as it did. I even got a caricature out of it. Bucket list completed.

In Stavanger, you will produce a new façade painting, LOL, at Rogaland Kunstsenter. Will it be a continuation of LOLERZ (+ +)?

Yes, you could say that. The titles are obviously connected. I will paint it in the same technique as before and try to introduce Norwegian Black Metal, in relation to the moral panic of the Christian Right. It could be a beautiful encounter, I think, as a kind of reference to the rapprochement I mentioned earlier.

When we started talking about a show at Prosjektrom Normanns and Stavanger, I know that you were triggered by the context and began thinking about site-specific works. How is your relationship with Norway and Stavanger, and how is it expressed in the exhibition?

I like site-specific works that don’t try to point to what is wrong with a site, in a moralistic sense. In Stavanger, I want to experience how oil, like the spirit in a bottle, goes up in smoke, how it is transformed and assumes the form of something volatile – a nothing-lasts-forever type of thing. I also have an idea of taking the dirt in Stavanger and presenting it in the gallery in the form of a brick wall made of sponges. The performative aspect will be carried out in public space in Stavanger and transposed into the white cube. I will also bring a “Swedish death”, in the form of a Volvo emblem. Volvo is no longer present where I live now, so it’s about a sort of balance and about pointing to something that was a fixture for many years and no longer is so. Death by Nature, so to speak.

A vanitas motif of Volvo! I know that you are also working on paintings for the exhibition, with Smurf motifs. Can you talk about the process behind the paintings and also about the choice of titles and subject matter. I believe they also relate to your desire to approach Norway/Stavanger?

Yes, somehow I ended up thinking about cash and strategy. The Smurf as a type of reflection of a social structure felt interesting. That’s why I created two Smurfs, which, in some way, I find in Norway, the Oil Smurf (2015) and the Chess Smurf (2015). They are both highly identifiable characters in Norway. I made them using different techniques. The Oil Smurf is of course painted in oil, while the Chess Smurf is executed in mixed media of smoke bombs and acrylic, among other things. They constitute a diptych of a social order, perhaps.

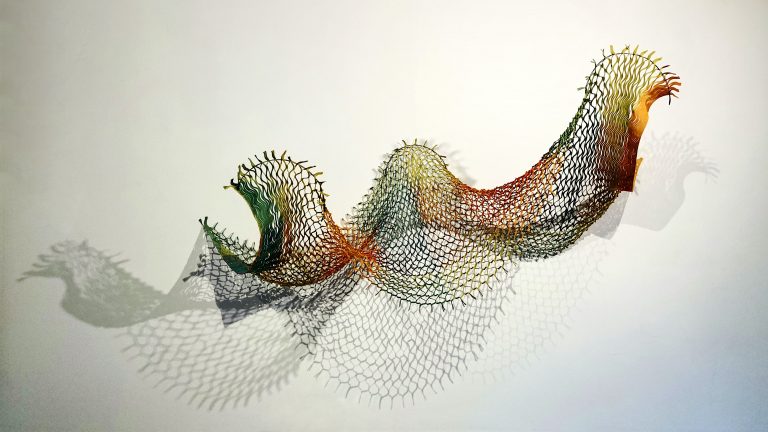

How long have you been working on these “smoke sculptures” and what do they mean to you? Do they signify different things depending on where you perform them? And how is smoke related to your paintings?

I have in fact made smoke sculptures since I was about ten years old. I used to smoke out my childhood neighbourhood. I suppose it had something to do with a desire to see something else than the normal, and to challenge the normalising glasses one uses in one’s everyday life. Needless to say, the smoke sculptures refer to different things. They are mainly related to the given architecture or the local history, for example. The overriding idea with these works is to create a larger playground, during a specific time frame, and then return to normal everyday life, without leaving any traces of what has occurred. In Stavanger, it will be black smoke based on what I referred to earlier, transience, GDP and oil.

(The interview is a translation of the pamphlet made for the exhibition at Contemporary Art Stavanger. Her you can see the original text and pictures)

Artist biography Klas Eriksson

Klas Eriksson lives and works in Gothenburg. He was educated at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm.